Historians of religion in early America ought to be shouting “Huzzah!” for the Congregational Library these days. Since 2011, Jeff Cooper and a team of scholars at this important research archive on Boston’s Beacon Hill have been gathering at-risk Congregational church records from basements, bank vaults, and private homes. The goal of the library’s New England’s Hidden Histories project is stunningly ambitious: to preserve, digitize, and transcribe tens of thousands of pages of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century church records.

I’ve been fortunate to serve on the steering committee for the program, which is led by Cooper and the Congregational Library’s executive director, Peggy Bendroth. Many of the key manuscript collections cited in Darkness Falls on the Land of Light are now available online through the NEHH portal, while many others are coming soon.

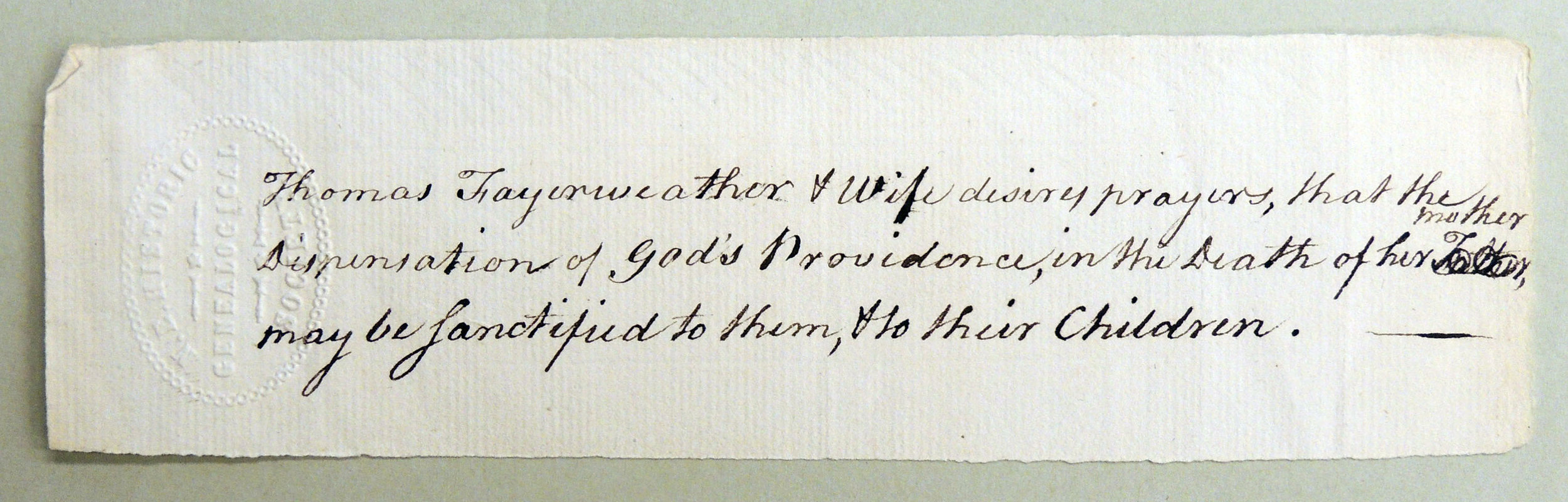

Testimony of Hannah Corey, April 5, 1749, Sturbridge, Mass., Separatist Congregational Church Records, 1745–1762, Congregational Library, Boston (available online at NEHH)

Highlights from the NEHH collection (so far) include:

- More than 500 church admission relations from Haverhill, Middleborough, and Essex, Massachusetts—all in full, glorious color!

- Church records from the “praying Indian” church at Natick;

- Ministerial association record books from nearly every county in Connecticut;

- Lists of men and women admitted to the First Church of Ipswich, Massachusetts, site of one of the largest religious revivals of eighteenth-century North America;

- Minutes from the Grafton, Massachusetts, church record book, with transcription, detailing the troubled pastorate of the ardent revivalist clergyman Solomon Prentice and his separatist wife, Sarah;

- Disciplinary records resulting from the bitter New Light church schisms in Newbury and Sturbridge, Massachusetts;

- Miscellaneous church papers from Granville, Massachusetts, featuring letters by the celebrated African American preacher Lemuel Haynes;

- And a wide range of sermons, theological notebooks, and personal papers by eighteenth-century Congregational clergymen, including luminaries Cotton Mather, Jonathan Edwards, and Samuel Hopkins.

Cooper and Bendroth have forged partnerships with New England’s leading history institutions, including the American Antiquarian Society and Peabody Essex Museum. And they have digitized An Inventory of the Records of the Particular (Congregational) Churches of Massachusetts Gathered 1620–1805, the indispensable guide compiled by Bendroth’s predecessor, Harold Field Worthley.

For teachers eager to show their students what seventeenth- and eighteenth-century history is made of; for undergraduate and graduate students seeking primary texts for papers; for genealogists searching for baptismal records of long-lost ancestors; for scholars engaged in major book projects—NEHH is now the go-to hub for online research on the history of New England puritanism and the Congregational tradition.

As with all digital history initiatives, NEHH is a work in progress. They’re always looking for volunteers to support their crowd-sourced transcription projects. It’s a great opportunity to involve students in the production of new historical knowledge. For more information, contact Jeff Cooper or Helen Gelinas, director of transcription.

Thanks to a second $300,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, Bendroth, Cooper and their colleagues at the Congregational Library will be churning out high quality digital images and transcriptions of rare Congregational manuscript church records for years to come. Congratulations, CLA! Huzzah!

To read more about the NEH grant, check out this article from the Christian Science Monitor.